Tensions over the UCP government’s move to open the Eastern Slopes of the Rockies to coal development have bubbled over recently, as well-known Alberta country singers added their voices to a growing chorus of opposition to the plan and a group of landowners went to court to seek a judicial review in hopes of forcing a policy reversal. More than 100,000 people have signed two petitions opposing the expansion of coal mining in the province. Here, Postmedia answers five common questions about Alberta’s coal policy, and how we got to this point.

1. What is the change that the UCP government made, and why are people upset?

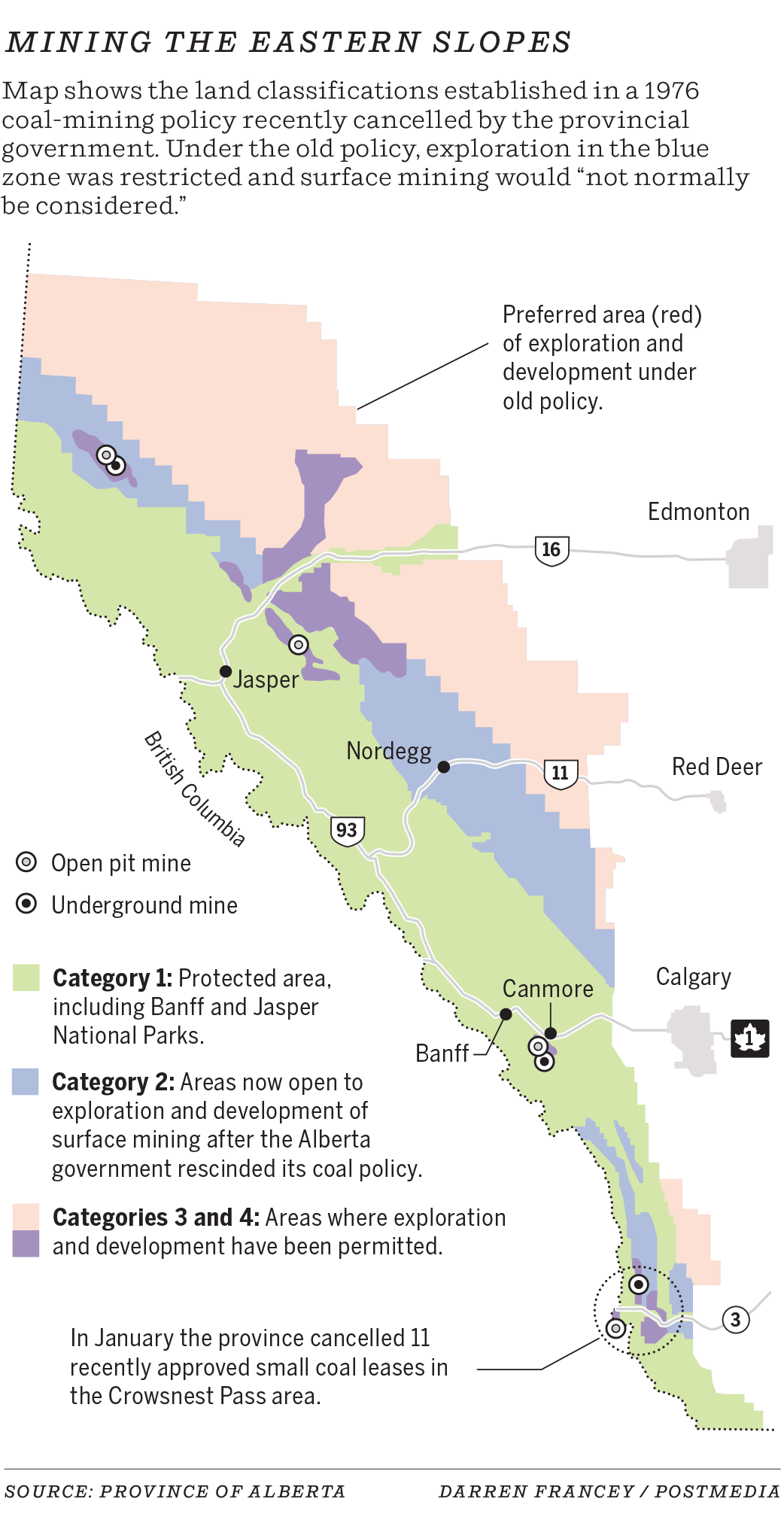

In May of last year, the UCP government rescinded a policy governing coal exploration and development in Alberta that had been in place since 1976. That policy included a land-use classification system that divided the province into four categories, dictating where and how coal leasing, exploration and development could occur.

While coal mining is still prohibited in Category 1 lands (the most ecologically sensitive parts of the province), rescinding the coal policy means an end to restrictions on Category 2 and 3 lands — which include large swaths of the Eastern Slopes and were previously protected.

According to the government, the 1976 coal policy was drafted before modern land-use planning and regulatory processes came into existence. It says the policy is “obsolete,” and that removing it simply means that all coal development projects will be considered through the existing rigorous Alberta Energy Regulator review process. In addition, those interested in acquiring Crown coal leases and pursuing exploration and development opportunities face the same restrictions as other industrial users — restrictions laid out in area plans such as the South Saskatchewan Regional Plan and the Livingstone-Porcupine Hills Land Footprint Management Plan.

However, environmentalists say much of the Eastern Slopes region is not covered under a land-use plan, so in the absence of the old coal policy, there is nothing to prevent coal companies from proposing and advancing plans for open-pit coal mining in once-protected areas. Coal development in these areas would jeopardize fish and wildlife populations and raises concerns about water usage and quality, they say.

2. How many mines are proposed?

There are currently six open-pit or “mountaintop removal” mines proposed for southwest Alberta that are already in varying stages of the regulatory process. Not all of these mines are affected by the change in government coal policy — Grassy Mountain, the mine that is farthest along in the development process and which is currently under review by a joint federal-provincial panel — was proposed in 2013, long before the 1976 plan was rescinded. If built, this mine will be on Category 4 land, which always allowed for potential coal development, and in fact the particular land in question was mined 60 years ago and later abandoned.

Montem’s Tent Mountain project is also proposed for a site that was previously mined, on Category 4 land.

However, some of the other proposed projects do benefit from the government’s policy change. Atrum Coal, for example, wants to build a 16,000-hectare open-pit mine in a Category 2 zone, where such mines previously were not permitted. The proposed Cabin Ridge project is also on former Category 2 land.

Earlier this week, Alberta Energy Minister Sonya Savage announced the province will cancel 11 recently issued coal leases and pause future lease sales, a reaction to growing public backlash toward planned coal development. But the cancelled leases do not affect any of the six proposed mine projects already in development, and environmentalists point out the cancelled leases amount to just 0.2 per cent of the land currently leased to coal companies.

3. But wait, aren’t we trying to phase out coal?

Alberta is aiming to phase out greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired electricity generation by 2030. But there are two types of coal — thermal coal, which is used to produce electricity, and metallurgical coal, which is used to make steel. The companies that are proposing new coal mines for Alberta aim to produce metallurgical coal, which wouldn’t be used domestically but would be exported to Asia where population growth and urban expansion is driving market demand.

The proposed mines do have some local support. The municipality of Crowsnest Pass is in favour of the Grassy Mountain project, which it believes will bring high-paying jobs to its residents. Grassy Mountain has also received letters of support from all of the Treaty 7 First Nations.

4. What is selenium?

Selenium is an element found in the earth’s crust that can be toxic in large quantities.

In 2017, Teck Resources, which operates just on the other side of the provincial boundary, on the B.C. side of the Crowsnest Pass, was fined $1.4 million by the federal government for selenium discharges from its coal mining operations, which were linked to deformities in a tributary of the Elk River.

Those who oppose the construction of new coal mines in Alberta worry that a similar thing could happen here, and warn about the effect selenium pollution could have on threatened species in the area, such as the west slope cutthroat trout. Opponents also worry that selenium pollution could pose a risk to the drinking water of communities downstream from the proposed developments.

Benga Mining, the Australian company behind the Grassy Mountain project, says its mine proposal has been specifically designed to safely and effectively manage selenium. The company also says it has developed a fish monitoring program and a fisheries offset plan to protect the local population of cutthroat trout.

5. Where do we go from here?

In cancelling the 11 coal leases earlier this week, Energy Minister Sonya Savage said her government has listened to the concerns of Albertans. She said the pause on future lease sales will ensure the interests of Albertans are protected, though she did not commit to restricting development on the Eastern Slopes.

“Coal development remains an important part of the western Canadian economy, especially in rural communities, but we are committed to demonstrating that it will only be developed responsibly under Alberta’s modern regulatory standards and processes,” Savage said.

In a Calgary courtroom this week, landowners, First Nations, ranchers, municipal officials and environmentalists will continue to try to convince a judge to grant a judicial review into the province’s decision to overturn its decades-old coal policy.

In the meantime, the public hearings portion of the joint review panel into the Grassy Mountain project have wrapped up. The panel’s decision on whether to approve the project is not expected until the end of 2021.

Twitter: @AmandaMsteph

You can read more of the news on source