[ad_1]

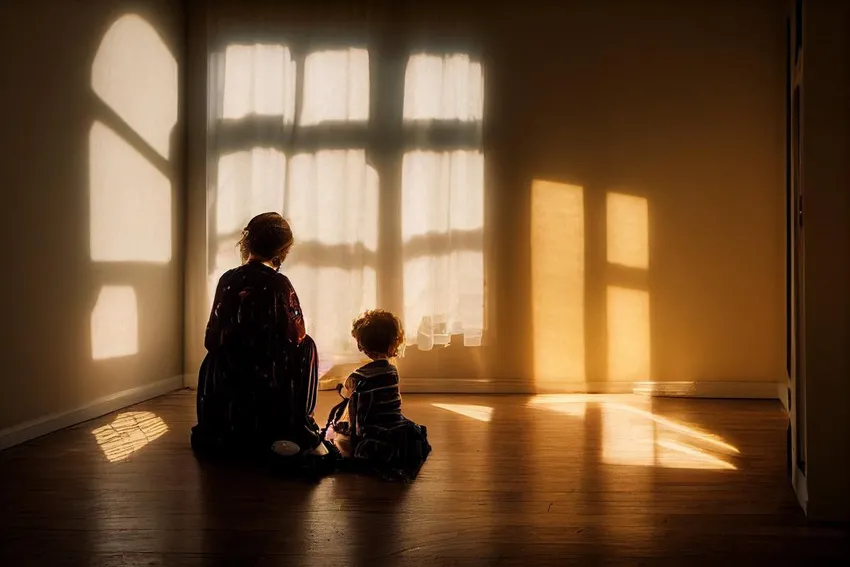

A distraught young mom stares out the window in a barren room, holding a baby. The striking image is meant to evoke sympathy for a charity campaign, to prod the viewer into asking who this poor woman is and how they can help her.

But there’s a catch: the woman isn’t real.

Furniture Bank, a Toronto-based charity that collects used household items for people in need, switched to artificial-intelligence-generated images in its 2022 holiday campaign, raising a host of ethical questions along with donations.

Executive director Dan Kershaw said the lifelike scenes are meant to illustrate the desolation and isolation of clients without objectifying or dehumanizing real people. Essentially, the charity claims to have found a way around the sticky “poverty porn” strategy charities have relied on for decades.

“Poverty porn is the primary way which our sector has to do their campaigns, in order to get the attention of the donors,” Kershaw said. “If they didn’t do it, nobody would look at their emails or their social media ads or the like, and they wouldn’t raise funds.”

He said Canada’s charitable sector is in crisis, with more than 86,000 charities competing for funds at a time when donations are in decline and the number of people who need help is rising.

Studies have shown images depicting negative emotions generate significantly bigger donations than those with smiling faces. But there has been recent pushback against so-called poverty porn, which critics argue can perpetuate harmful stereotypes and retraumatize its subjects.

The families Furniture Bank helps are often transitioning out of homelessness or a period of crisis. Kershaw said he could never bring himself to ask people to pose for photos in that state, so instead, the charity has traditionally hired photographers to shoot happy clients with their new furniture after they’ve been helped.

This year, Kershaw was able to take stories written by real clients, input them into AI photo program Midjourney, and create 40 images with the help of AI architect Pablo Pietropinto, who added photorealistic tweaks. This allowed Furniture Bank to depict some of the darkest moments in clients’ lives without identifying them in any way, finally telling the story Kershaw wanted the public to hear.

“We’ve got people sleeping on floors, we’ve got children curled up in nests of clothing as their bed,” he said. “It’s a form of hidden homelessness that, unless you’ve lived that way, it’s very hard to imagine living that way.

“I’m a father. I could never ask a mother, ‘Would you please have your child curl up in a bed of clothes so this stranger photographer can take photos so that we can go and raise funds.’ That (would be) logistically, economically and morally wrong.”

He said the AI approach lets clients play an advocacy role without being harmed by images or words that will stick with them forever. It also saved his charity about $30,000.

The rapid spread of programs like Midjourney, DALL-E and Lensa AI in 2022 has made it easy for just about anyone to generate elaborate images in seconds. More than 17 million people have downloaded Lensa AI since its “Magic Avatars” feature was released in late November, turning people’s smartphone selfies into fantastical portraits.

Jon Dean, a sociology professor who studies images of homelessness, said AI is a step in the right direction in this case, but it doesn’t necessarily elevate Furniture Bank’s images out of the “poverty porn” realm.

“I think they solved half of the problem,” Dean said. “By not identifying individuals, they’ve certainly solved an ethical conundrum, which is how do you show pain and suffering of human beings without exploiting specific human beings.”

The unsolved problem is that a campaign based around decontextualized images still puts the focus on individual suffering, rather than the root causes of the suffering. Regardless of whether the images are technically real, Dean said this approach portrays a “depoliticized, one-dimensional view” of poverty, which is a common critique levelled at the charitable sector in general.

Some charities even use real photographs of actors depicting scenes of poverty, which walks a similar line.

“They have a tendency to centre the fact that somebody is suffering from a lack of something — in this case, furniture — rather than asking questions about why they might be lacking that in the first place,” Dean said.

Some of AI’s loudest critics are photographers, who either say they have had their work stolen by image generators, or worry that the ease of creating AI images will ultimately devalue their own photos or put them out of work.

Henry Schnell, president of the Canadian Association for Photographic Art, says it’s important to ask where the original data came from to form each image. In most cases it’s impossible to know, because the programs scrape massive archives of images from across the internet to match users’ input cues. Midjourney founder David Holz acknowledged in a September interview with Forbes magazine that his company did not seek consent from living artists or for work that’s still under copyright.

Schnell said photographers should not subject real families to “poverty porn” setups, but argued Furniture Bank’s approach swaps one set of ethics for another.

“The window and the kid and the bed must be coming from another image of some sort,” he said. “It’s not just the guy sitting at the computer that has drawn that.

“From an ethical point of view, you’re plagiarizing. You’re stealing. Yes it saves money, at what expense?”

The charity’s website acknowledges AI is “spawning fierce debate in art circles,” but the strategy has garnered mostly positive attention.

Kershaw said that while donations are roughly on par with last year so far, Furniture Bank has never seen so much engagement with a holiday campaign — even IKEA has reached out asking how to help. Nine other Furniture Bank locations have asked for permission to use the images, and he’s scheduling a webinar to teach them how to make their own.

Stowe Boyd, who researches technological evolution and the digital economy, said we are becoming acclimated to a world in which we have to question every image we see online.

While plagiarism has always existed in various forms, Boyd said AI provides another way to “degrade the currency of authenticity” in photography and writing. Whether authenticity matters is a more complicated question. In his view, a news reporter quoting a fictional straw man in an article, for example, or a charity pretending an AI image was real, would cross an ethical line.

Boyd said Furniture Bank’s campaign approaches — but stops short of crossing — that line.

“They’re attempting just to put an idea in your head and to provide a visual aspect of what it is they’re trying to get across as a message. Maybe that’s in a zone of acceptability, because of course we’d like the charity to save money, and these tools work. And in a sense, who cares if there’s really a ‘Jane Bowers’ or not?” Boyd said.

“I think they’re falling ethically in the right place. But I don’t think that means that other people will.”

[ad_2]

You can read more of the news on source