[ad_1]

One summer we flew deep into northern British Columbia, to a lake surrounded by such vast wilderness that for an hour we looked down from our floatplane and didn’t see any sign of human activity: no roads, no power lines. Just a great forest and now and then a glimpse of all the life that it contained: wild rivers, ragged white mountain goats on black cliffs, a moose surging out of a lake, a bear and her cubs, turning rocks high on a scree slope.

We were with two other families, making a small camp in a clearing on the shore of a mountain lake that held big rainbow trout. The lake was on a high plateau. A rough, grey mountain peak stood to the south, and across the water far to the west was a distant, snowy range, illuminated, then cast in silhouette by the setting sun. To the north and east lay an undulating, undisturbed forest of pine and spruce. After the sun went down the lake glowed, as if it was releasing light back into the sky.

Standing at the campfire, with sparks spiralling toward the faint, emerging stars, I could see a cedar canoe anchored off a nearby point, an elegant swoop of green on a wild canvas of black and blue. I knew it was tethered to the soft, weedy bottom of the lake by a stretch of yellow rope tied to a rock. There was an almost imperceptible offshore breeze. Not enough to ruffle the surface, but persistent enough that the anchor line was pulled tight, as if the canoe was trying to drift with a tide into the night sky.

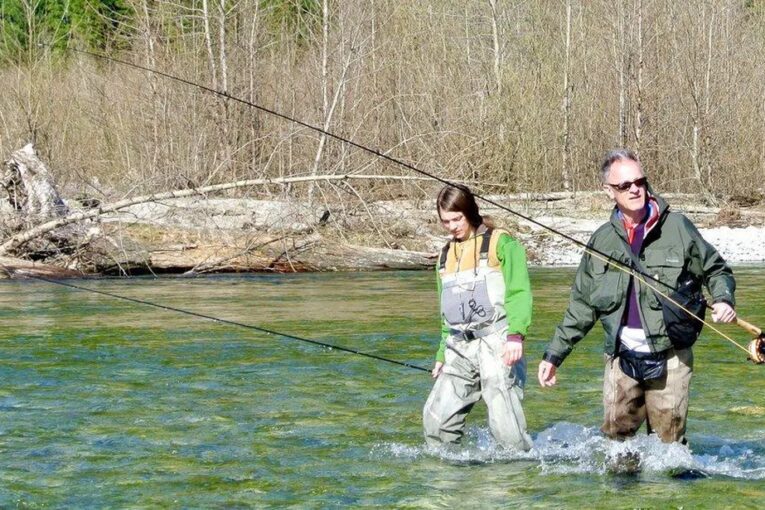

A young woman with a fly rod stood to cast her line over a patch of water tinged green from a bed of weeds growing in lime-rich mud in the shallows.

I watched as my daughter slowly retrieved her line and then threw it out again, far over the water. Emma had been casting all day, ashore only for a quick lunch, and seemed oblivious to the oceanic darkness rising around her. I knew why.

Over that shallow point earlier in the day she had cast a big, black leech pattern made of rabbit fur, leaning into the cast and ducking as the heavy fly shot past her head. Drawing the fly back along the drop-off, retrieving it slowly so that it swam through the water with a waving motion, she felt a violent pull. A rainbow trout, possibly one of the 18-pounders the lake held, yanked the rod tip into the water.

The butt of the rod kicked into her stomach and the line went tight as a great weight surged into the depths. Straining against it she felt the cork handle twisting in her hand as the trout fought.

Fly fishing is a visceral experience, where sight and sound and light are all stimulants, but it is the sense of touch that is most electrifying. The rod vibrates when a fish accelerates, it jerks when a fish shakes its head; it transmits heaviness from the sluggish weight of weeds gathering on the line, and then a sudden slackness signals that a hook has lost its hold — or the line has broken.

Emma had been startled by the power of the big fish, the biggest trout she’d ever hooked, and watched amazed as the line sliced across the flats, hissing as it cut the surface.

It is hard to guess the weight of a fish that is unseen in the depths. They can feel much bigger than they are, but this one jumped once, up high, coming down heavy. It was one of the great fish we knew the lake held. A hunter, a top predator, had come in from the depths to cruise over the weed bed, and now it was racing away trying to shake the leech caught in its jaws.

Emma just hung on, hoping it would slow before she was spooled, before the line was stripped completely from the violently spinning reel. Then the trout changed direction and there was a slow, wet drag on the line as the fish ran through a weed bed. The weight built up as weeds accumulated on the line, and then the fish was gone, the line slack and lifeless in an empty lake.

And she couldn’t quite believe it: not then, not hours later.

So she was back, anchored in the same place over the luminous marl bed, triangulating her canoe’s position with a tall tree, the tents, and a mountain. She was trying to reconnect, searching with hundreds of casts, buoyed by the hope that the trout just might be there. Again. Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

She had caught some big trout of five pounds, but wanted one of the giants that prowled the lake. We’d flown high into the mountains just to have a chance at such large trout, after all. As I watched her cast, my eyes slowly filling with the night, I realized after a childhood spent traipsing around with me to countless lakes and frog ponds, she had become a true fly fisher.

She was still a teenager, but after fishing for surfperch on oily docks or for small trout in cold, windblown lakes where blackflies swarmed us and bears left tracks in the mud along the shore, after waking in tents to listen to owls call in the lonely darkness, and hearing billions of crickets shrilling along a desert river, a big trout had raced off into the dark water with her heart.

She was caught now, as I had been as a boy, by the loss of a great fish.

That night she came in pleased with the trout she’d landed, including one that jumped over the canoe, forcing her to duck, but still shaking her head in wonder at the huge rainbow that got away.

“A slab,” she called it.

Her younger sister, Claire, had fished with her through part of the day on the mountain lake, but hadn’t lost a trophy and was happy working around the campfire, helping to make dinner. For her fly fishing was mostly still just a means to be with people she loved in the outdoors. Though she was always happy to go out on the water with me, catching fish just didn’t seem that important to her.

I realized that maybe she didn’t need to catch fish because she’d had success early and that gave her the feeling that fish were out there, just waiting for her.

On a summer day a few years earlier, while we were staying in a cabin on a small lake, I left Claire with Maggie as I readied a rented rowboat that was too small for three. While Emma and I fussed with our tackle, Claire lay down on the dock and peered through the wooden planks. And there beneath her a secret world opened. Several big trout were finning below.

As we rowed away, Claire stood up, took her rod, and flipped out a fly, getting it to drift into the shadows, into the hidden world she’d discovered.

A pair of fishermen outfitted in expensive fly fishing rods, fishing vests with multiple pockets, and baseball caps that declared their loyalty to Orvis, a high-end tackle manufacturer, were coming in.

“Nothing,” said one of them as our boats passed. He held his hands up as if to say the fishing gods had abandoned them.

Just then Claire’s rod bent deeply. A rainbow trout leaped between the two boats and landed with a splash before dashing back under the wharf. Claire held on. The fish pulled the rod tip into the water and bent it under the wharf, then jumped on the other side of the dock.

Claire was looking down into the water in front of her, and the trout was thrashing the surface behind her. There was a lot of confusion as all the men started shouting advice at once and Maggie and Emma cheered.

“Hooray!” shouted Emma.

Claire swung her rod tip around the end of the wharf so she was facing the trout, and she refused to yield. By the time I scrambled back onto the dock, the trout was splashing in the water below her feet. I dipped the net in and lifted a four-pound rainbow trout; big by anyone’s standards.

The two anglers who had just circumnavigated the lake looked dejected.“We didn’t get a bite all morning,” said one, pushing back his Orvis ball cap.

I pulled out the fly and Claire held the fish gently, then released it. She looked amazed as it bolted free. She has always fished with serenity because of that day, knowing that a big fish will come to her when it will.

On our last night on the mountain lake a pack of wolves began to howl. The girls listened, wide-eyed, and then Claire howled back. After a moment the wolves answered, curious, excited, questioning the high sweet voice calling to them in the gathering darkness. Emma joined in and the girls and the wolves sang to each other, then the forest grew silent.

[ad_2]

You can read more of the news on source