Amidst the flurry of headlines about the 2017 federal budget, Ontario held its first cap and trade auction last week. While it will take a few more weeks for the results to be calculated and posted, let’s review why Ontario decided to price carbon pollution in the first place, and why it’s the right choice.

Carbon pricing is an effective environmental and economic tool. Often touted as the “first best” climate policy by economists of all stripes, the OECD backed up these assertions by looking under the hood of 15 different countries and their policies to combat carbon pollution, also referred to as greenhouse gas emissions, concluding that, “market-based approaches like taxes and trading systems consistently reduced CO2 at a lower cost than other instruments.”

Carbon pricing works because it sends a policy signal that directly affects behaviour, rewarding those who make choices that reduce carbon pollution. What’s more, it allows for flexibility in how heavy emitters reduce emissions, either by purchasing allowances or turning to clean innovations, which help to decrease the amount of greenhouse gases emitted. Those approaches include technologies and services such as: heat pumps, energy storage, renewable natural gas, energy efficiency and more. And with the incentive for innovation, Canada can spur its clean technology industry forward, in an effort to grow its share of a global market opportunity estimated by Analytica Advisors to be worth US$3 trillion by 2020.

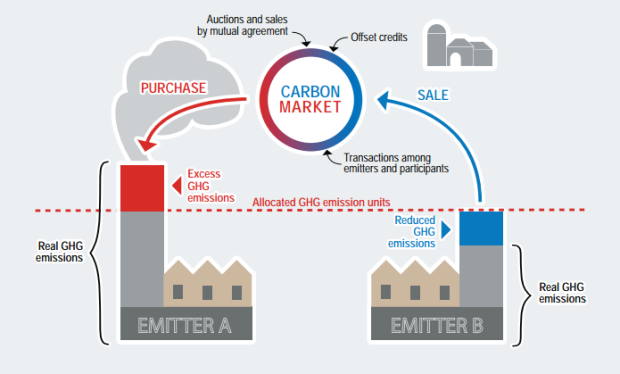

How a cap and trade system works. Source: Ministry of Environment and Climate Change, Government of Ontario.

In December, most of Canada’s premiers and the prime minister agreed on a new national climate plan, the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, outlining a benchmark to have carbon pricing systems in place across the country by 2018. The plan gives provinces and territories “the flexibility to design their own policies to meet emissions-reduction targets, including carbon pricing, adapted to each province and territory’s specific circumstances.” Ontario was a signatory to this approach, and has chosen to implement a cap and trade system of pricing carbon emissions.

The cap refers to a limit on greenhouse gas emissions released into the atmosphere. Companies pay penalties if they exceed the cap, which gets stricter over time. The trade refers to a market for companies to buy and sell allowances that permit them to release greenhouse gas emissions. Trading gives companies a strong incentive to save money by cutting emissions, because they don’t have to pay for allowances.

Ontario has chosen to link its cap and trade system with its neighbour to the east, Quebec, and California, the world’s sixth-largest economy according to the International Monetary Fund. Under the Western Climate Initiative, the three jurisdictions will take a regional approach to tackling carbon emissions, while spurring investment in clean-energy technologies, creating an economy based on clean growth. While Ontario’s decision has been met with robust debate, it makes sense for the province.

Impact modelling and analysis of Ontario’s preferred carbon pricing approach clearly indicates that participating in the Western Climate Initiative will have the least impact on Ontario’s economy. The linked cap and trade system is expected to add $13/month in costs for the average household (increases in natural gas for home heating and at the fuel pump for your car) compared to $50/month under an unlinked cap and trade market or a carbon tax. It appears to be the same story for reducing emissions— the greatest net reductions are projected under a linked system, at 18.42 million tonnes of CO2e versus 12.7 million tonnes.

The Western Climate Initiative is based on lessons learned through other carbon trading systems, most notably the European Union Emissions-Trading System. As Clean Energy Canada uncovered in the report, Inside North America’s Largest Carbon Market, deliberate policy levers were built in to ensure the strength and robustness of the system, such as the inclusion of a price floor (to prevent the market price for allowances from dipping below a certain threshold).

Another policy lever worth mentioning is the “compliance period,” which generally is three years. The end of a compliance period marks the occasion at which each regulated facility must turn in their allowances equivalent to their total carbon emissions. (These allowances also include early reduction credits or a limited number of offset credits, no more than eight per cent of the total compliance obligation, as per the Western Climate Initiative rules.) However, it’s also an opportunity to review the policy and how well it is working. Consultations are underway in both California and Quebec to explore potential improvements to the system in 2020, and even Ontario has started down that path.

So as speculation about the success of Ontario’s first cap and trade auction continues, let’s keep the big picture in mind: pricing carbon is an effective and economically sound tool to reduce emissions. And with the federal carbon pricing requirement coming into effect next year, Ontario’s commitment to cap and trade takes necessary action to cut carbon pollution—leaving room for improvements as needed, and at the least possible cost.

You can read more of the news on source